KABUL - For decades Ismail Temorzada's handmade Afghan carpets decorated people's homes around the world, but export problems and competition from Iran's machine-made products have left his business threadbare.

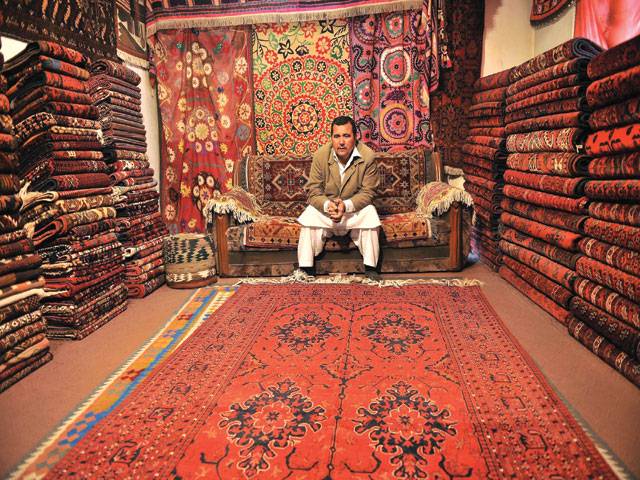

"My carpet sales are down, no one is buying hand-made carpets anymore," says Temorzada, 45, who has run a shop for more than 20 years in Kabul's once crowded and colourful Chicken Street bazaar.

"Iranian machine-made carpets are imported to Afghanistan at a cheaper price," he told AFP, dismissing them as lacking originality, durability and charm. But they are cheap and people buy them, and his sales have dropped by 70 percent over the past year, he says.

Carpets are Afghanistan's best known export, woven mostly by women in the north of the country. Displaying his best carpets, from Andkhoy in northern Faryab province, Temorzada said they cost 60,000 Afghanis -- about $1,300 -- but nobody is buying them now.

He wants the government to ban the importation of machine-made carpets from Iran -- or at least impose a steep hike in the import duty. "Recently, Afghan carpet businessmen had a meeting with President Hamid Karzai and the president told us that if we ban their carpets then they will ban all their products to Afghanistan.

"If we cannot ban the Iranian machine-made carpets we should increase the duty on the product from $10 a metre to $100, so that they cannot be imported to Afghanistan in great numbers and slowly will be reduced." Temorzada also wants the government of the landlocked and war-torn country to help the industry export its own products directly to clients around the world. At the moment, transport problems mean that most carpets are sent to neighbouring Pakistan for washing and cutting and are often then shipped abroad under Pakistani labels.

Afghan carpet making used to employ directly or indirectly six million people, or a fifth of the country's population, according to the export promotion agency of Afghanistan -- but that figure has dropped sharply. "The Afghan carpet industry is totally dependent on the international market," Mohammad Zarif Yadgari, deputy director of the Afghan Carpet Exporters' Guild told AFP. "There is no direct access (to sell) abroad -- if we export carpets they will be sent abroad from Pakistan through middlemen."

The value of carpet exports fell from $262 million in 2007 to $149 million in 2008, according to the Afghanistan Chamber of Commerce and Industries (ACCI).

In 2010, nearly 400,000 square metres of carpets worth $48 million were sold, but this dropped by half last year. However, while some businesses suffer, others are thriving.

"Since I brought Iranian machine-made carpets my business has boomed," said Kabul carpet dealer Mohammad Muzamil Yousufzai. "Because they are cheap and are sold at a reasonable price everyone can afford to buy them. The Afghan government says it is making moves to help local carpet makers.

"The government has started work on the construction of industrial parks for carpet businessmen for washing and scissoring," Motasil Komaki, deputy commerce and industries minister, told AFP.

Describing carpets as "Afghanistan's national industry", he said the parks would initially be built in four provinces -- Faryab, Balkh, Herat and Jawzjan. Weaving carpets was a main source of income for the millions of Afghans who fled to neighbouring Pakistan during Afghanistan's years of war, notably the 1990s civil conflict that was followed by Taliban rule.

About 80 percent of the exiles have returned home since the ouster of the Taliban government in 2001 and now a large portion of Pakistan's carpets are made in Afghanistan but sold as Pakistani, according to government figures.

Afghanistan, one of the poorest countries in the world, can ill afford to lose its main industry. Its economy has been supported by huge infusions of Western cash for the past decade as 130,000 US-led NATO troops help President Hamid Karzai's government fight a Taliban insurgency.

Kabul this month saw its biggest coordinated militant attacks in 10 years of war, leaving 51 dead after explosions and gunfire rocked the capital in a brutal reminder of how severe the security threat is. But the troops are due to leave by the end of 2014, and the economy is expected to be hit hard.

Friday, April 19, 2024

Iranian machines leave Afghan carpet industry threadbare

King Charles's cancer ‘eating him alive,' monarch unable to perform duties: Insider

1:02 AM | April 19, 2024

Mehwish Hayat says she would like to work with Aamir Khan

9:59 PM | April 18, 2024

What caused record-breaking rainfall in UAE?

9:58 PM | April 18, 2024

Donald Trump discusses Ukraine, Middle East, NATO with Polish President Duda

9:57 PM | April 18, 2024

'That'll be awesome,' Rohit Sharma on idea of Pakistan vs India Test series

9:17 PM | April 18, 2024

Hepatitis Challenge

April 18, 2024

IMF Predictions

April 18, 2024

Wheat War

April 18, 2024

Rail Revival

April 17, 2024

Addressing Climate Change

April 17, 2024

Justice denied

April 18, 2024

AI dilemmas unveiled

April 18, 2024

Tax tangle

April 18, 2024

Workforce inequality

April 17, 2024

New partnerships

April 17, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Advertisement

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024