I had been told I was number one on the terrorist hit-list, although who the terrorists would be was anybody’s guess. There are perhaps 25 militant groups which now call themselves ‘Taliban’ and any one of them could have been hired by my political opponents.

There had already been damaging smears, including the claim that I was part of a Zionist conspiracy to take over Pakistan. It was a dangerous allegation, and one that sounds crazy given my vehement opposition to drone strikes and the so-called ‘war on terror’. But the threat to my life was all too real.

It is an irony, then, that a serious assassination attempt was prevented only by an accident – and the fact that I spent the closing days of the Pakistan election campaign in a hospital bed.

The fall that nearly killed me quite possibly saved my life.

The British public might struggle to understand the energy and the chaos of that campaign. The meeting in Lahore where I fell in May was the first of nine separate rallies scheduled for that night.

The following day I was supposed to be speaking at a further 13, spaced along the old Grand Trunk Road from Lahore to Islamabad. About a quarter of voters live along that route.

We were drawing massive crowds and I was getting mobbed. Thousands were coming to hear me speak on behalf of our party, the Pakistan Movement for Justice, and we didn’t have the means to handle the spontaneous exuberance of the crowds. We were losing control.

The authorities had already warned me that my life was at risk, and I had been given the highest level of police security.

One safety measure was having me speak from a platform about 24ft above ground. This provided some protection from a potential bomb blast and also stopped passionate youths from climbing on to the stage.

There were no steps, so instead a forklift truck was used to raise me up to the small platform to speak.

And this is how I nearly met my end. The fork-lift rose in a series of jerks and the securitymen surrounding me formed a barrier. This meant I could not see there wasn’t a guard rail around the platform.

Losing my balance, I leant over to where I thought the safety barrier would be – and grasped at thin air. I somersaulted downwards, landing on my back from a height of about 18ft. The next thing I knew I was coming round in hospital, with doctors stitching up a head wound.

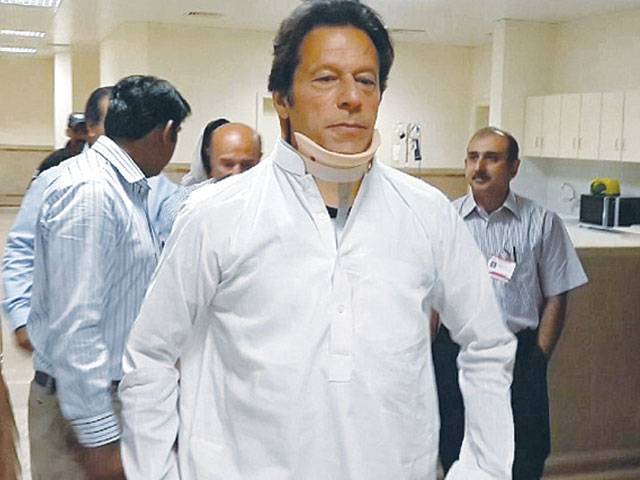

I also suffered a punctured lung, a crushed vertebra, three more chipped or fractured vertebrae, and concussion. I was lucky to be alive. My great fear as I lay there was that I was going to be paralysed.

I’ve always been fit; I’m now 60 and I’ve never known a life where I wasn’t in control of my body. I found myself prey to morbid thoughts, something completely out of character. I thought in particular about the victims of drone attacks and terrorist bombs. We always hear about the dead, not so much those who end up maimed. That was my great fear: not death, but being disabled.

As I regained consciousness, however, I started feeling all my toes, fingers and limbs, and I realised I hadn’t lost any sensation. My relief was intense.

Later, CT scans showed I had indeed come very close to being paralysed. The bullet-proof vest I’d started wearing only a few days earlier had acted as a cushion, and absorbed some of the shock of the fall.

I knew I was fortunate in more ways than one. The Almighty had been looking out for me that night. I could easily have sustained brain damage.

But there was something else, too: if I hadn’t been in hospital I could have been dead. Pakistan’s home minister came to visit and told me of an assassination attempt scheduled for the day after my fall.

At the same time, it was frustrating. We were coming to the end of the biggest election campaign in Pakistani history, and we had touched the hearts of the masses.

Other parties were pushing traditional candidates, what we call ‘electables’ – urban property magnates and rural feudal lords, the people who go into politics to make money, not to change people’s lives. They also switch sides regularly, not for political reasons, but because they think it’s in their personal interests to do so.

We will never have true democracy while MPs get into parliament by selling their services to the highest bidder, and where people vote for candidates rather than the manifesto of a party. We need to lose candidate-based politics.

We were different – the only party in Pakistan’s history to choose its candidates through internal elections. Almost 80 per cent of ours had never contested an election before and 35 per cent were under 40. They really were a refreshing change, and support was surging.

Yet just as the campaign was about to reach its peak, I found myself in hospital, unable even to read newspapers or watch television. Meanwhile, doctors couldn’t agree what treatment offered the best hope of a full, long-term recovery.

Thank God, in the end the ‘rest’ faction won, as opposed to those doctors who wanted me to undergo an operation. I have recently spent some time in England, attempting to rehabilitate my back after three months spent mostly lying in bed.

My fitness undoubtedly helped me recover quicker. Another factor has been the fact that I got injured several times as a fast bowler, so I have the advantage of knowing how to bounce back.

The support I’ve had from my family, friends and ordinary Pakistanis has been overwhelming. I was touched to discover there were crowds camping outside the hospital and praying for my recovery.

My ex-wife, Jemima, the mother of my two sons, called immediately after hearing the news, worried about the impact the TV images would have on our boys. My sisters, one of whom is a doctor, and my nephews were all at my bedside. There is much to be optimistic about. Yet the discovery that I had avoided an assassination plot serves to illustrate that Pakistan’s multiple crises are as serious and threatening as ever.

To begin with, there is no doubt that this was the most rigged election in Pakistan’s history, an election in which every party that participated has alleged massive fraud was committed. We know this to be true.

Mobile phones and social media have changed everything: people were able to film the ballot-stuffing and post videos of it on the internet. We have never had such a turnout of young voters and women – so the result, when it came, was a farce.

Within a day or two there was a spontaneous street movement to have the result overturned. But my party and I decided that we were not going to fan the flames because Pakistan’s situation is already so dangerous and unstable. Since the election, two of our party’s MPs have been assassinated.

There have been bomb blasts and dozens of killings of civilians and ordinary police officers especially in the KPK – Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (formerly known as North-West Frontier Province) – one of four in which my party has formed the government.

In these circumstances, we’ve decided that rather than pushing for mass protests, we will demand that the Supreme Court and the Election Commission conduct a proper investigation into the results in four sample constituencies so that the democratic process goes on while an investigation ensures that at least the next election is free and fair.

After the 2008 elections, when we petitioned the Supreme Court to correct and update the voters’ list, the court discovered that out of 80 million registered voters, there were 37 million bogus votes. We were supposed to stop this type of fraud because it was the first election to be conducted by an independent judiciary. We had thumbprint IDs on ballot slips. But sadly the judicial officers became part of the problem.

Establishing democracy is a slow and arduous process: look at what is happening in Egypt. But it’s vital that we never go back to military dictatorship. (I always thought the last dictator, Pervez Musharraf, was crazy to come back to Pakistan from his life of luxury in London. Never before has an army chief been hauled in front of a court of law. Now he’s facing a murder charge. I hope his trial will deter others of his ilk from trying to seize power.)

Pakistan’s biggest impediment to moving forward and achieving its potential is terrorism. Yet still this nation is unable to tackle the underlying causes: the war in Afghanistan, and the drone strikes.

To anyone who knew the country even ten years ago, the level of extremism and violence now is almost unimaginable. It is fuelled by the belief that in attacking militants in tribal areas, the army and the government have become tools of American policy. Every time there is a drone strike, there are revenge bomb attacks in the settled areas and cities, especially in the KPK.

Drone attacks approved by the Pakistani government – and it is an established fact that Musharraf gave his permission for them to be carried out – have enabled militants to justify their call for jihad, and this has led to suicide bombings, our national scourge.

Each drone attack, each operation against militants in tribal areas leads to more Pakistani dead, and the level of violence, along with a surge in extremism, will lead to a radicalisation of our society. It will only diminish when Pakistan starts to control its own territory and its destiny again, and disengages from this American-led war.

Last month in the High Court in Peshawar, in a case brought by families of drone attack victims and supported by my party, the judge forced the government’s chief representative in the autonomous tribal area of Waziristan to produce a statistic we had often demanded but never received: how many people, militant or civilian, have been killed by drones.

What he said was horrifying: in the past five years only 47 militants have been killed, while the number of ordinary Pakistani victims has reached 1,500 – and that does not include the 330 now missing limbs.

Yet I still have hope. Once again, I face each new day with excitement. I was hugely cheered when Nato General Nick Carter said recently that we should have been talking to the Taliban ten years ago. That’s what I’ve been saying for many years – the only way out of this crisis, and to rebuild our country, is to reach a political settlement.– Daily Mail

Friday, April 19, 2024

The fall that nearly killed me possibly saved my life

Formula 1 returns to China for Round 5

9:05 PM | April 19, 2024

Germany head coach Julian Nagelsmann extends contract till 2026 World Cup

9:00 PM | April 19, 2024

IMF urges Italy, France to spend less, Germany to loosen purse strings

8:57 PM | April 19, 2024

PM calls UAE president, admires Emirati leadership's response to recent Dubai rains

8:55 PM | April 19, 2024

Church leader calls for including Christians in Gandhara Corridor

8:50 PM | April 19, 2024

A Tense Neighbourhood

April 19, 2024

Dubai Underwater

April 19, 2024

X Debate Continues

April 19, 2024

Hepatitis Challenge

April 18, 2024

IMF Predictions

April 18, 2024

Kite tragedy

April 19, 2024

Discipline dilemma

April 19, 2024

Urgent plea

April 19, 2024

Justice denied

April 18, 2024

AI dilemmas unveiled

April 18, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Advertisement

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024