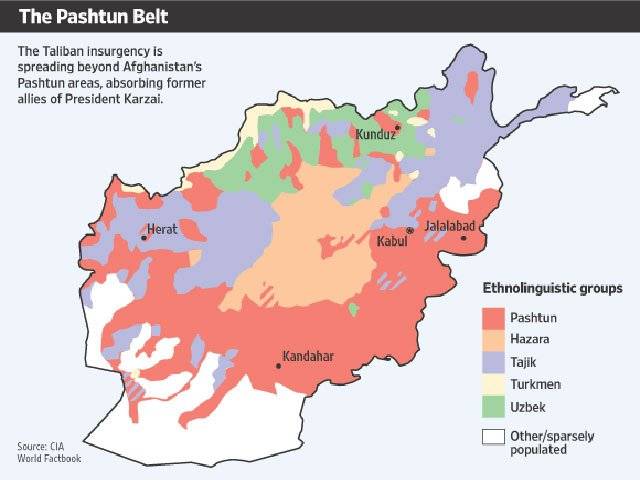

Ghulam Yahya, a former mayor of this ancient city along the Silk Road, battled the Taliban for years and worked hand in hand with Western officials to rebuild the country's industrial hub. Now, Mr. Yahya is firing rockets at the Herat airport and nearby coalition military headquarters. He has kidnapped soldiers and foreign contractors, claimed the downing of an Afghan army helicopter and planted bombs in central Herat including one that killed a district police chief and more than a dozen bystanders last month. Mr. Yahya's stranglehold over the outskirts of Herat has destabilized a former oasis of calm and relative prosperity. "The security situation here is critical," said Herat's current mayor, Mohammed Salim Taraki. Ghulam Yahya, former mayor of Herat, once worked with Western officials. Now he sides with the Taliban. The warlord's odyssey from friend to foe shows how disillusionment with the Western-backed administration of President Hamid Karzai has pushed even some former enemies of the Taliban into the insurgency. Violence is rapidly spreading beyond the ethnic Pashtun heartland of southern and eastern Afghanistan, where much of the countryside already is in rebel hands, into parts of the country that were considered safe just a few months ago. Widespread anger over alleged fraud in August's presidential elections -- where President Karzai is leading with 45.8 percent of the vote according to the latest partial count -- has deepened this alienation. Though President Karzai has tried for years to woo back insurgent commanders, only a handful have switched sides. Many more tribal leaders who had supported Kabul now cooperate with the Taliban, military officials say. In his strategic assessment of the war this week, General Stanley McChrystal, the top U.S. and allied commander in Afghanistan, described the situation in the country as "serious," warning about the Taliban's growing strength and the need to build more credible Afghan government institutions. An ethnic Tajik, Mr. Yahya is perhaps the most prominent non-Pashtun Afghan insurgent chieftain working with the Taliban. It isn't a natural union: When the Taliban conquered Herat in 1995, Mr. Yahya, then the city's mayor, had to flee to exile in Iran. He later took part in the anti-Taliban militias that fought the radical Islamist movement. After the Taliban regime's demise in 2001, Mr. Yahya returned to Herat to supervise public works in the provincial administration. It's only in the last year or so that Mr. Yahya, who fell out with Kabul, joined his former enemies. "Ghulam Yahya was not a Taliban," said General Ekramuddin Yawar, the Herat-based national police chief for western Afghanistan. "But now he has become one." An illiterate but cunning mujahedeen commander, the bearded Mr. Yahya was a scourge of Soviet occupation forces here in the 1980s. Now in his 60s, Mr. Yahya appears to be equally determined to fight the American and NATO coalition troops. "The foreign forces came here in the name of supporting the Afghan government and helping the reconstruction," Mr. Yahya said last month in an interview with an Afghan reporter working with The Wall Street Journal. "But, instead, they are only looking after their own interests, disrespecting Afghan culture, and bombing and killing innocent people all over the country." Until recently, most of that fighting was limited to ethnic Pashtun south and eastern Afghanistan, the Taliban's stronghold. The Pashtuns, who make up 42 percent of Afghanistan's 34 million people, account for the vast majority of Taliban militants. Persian-speaking Tajiks, more than one-quarter of Afghanistan's population, have traditionally followed a less rigid form of Islam, as did the Turkic Uzbek minority. But now, as frustration is mounting with the slow rebuilding, endemic corruption, and the tactics of Afghan and foreign soldiers, non-Pashtun militants like Mr. Yahya have sprouted up alongside their former Taliban enemies in northern and western Afghanistan. Unlike in the south and east, security here is maintained not by the U.S. military but by European allies like Italy, Germany and Spain that place much tighter restrictions on their soldiers' involvement in combat. Like Herat, the northern city of Kunduz, a gateway to the Tajikistan border, was recently rocked by explosions that killed senior Afghan officials. Western forces there clashed with an Uzbek militia last week. The escalating violence in the north and the west poses a major challenge to the 60,000 American troops in Afghanistan, already stretched thin trying to curb the militancy in their own deployment areas. Containing it will require a new approach by whoever emerges as Afghanistan's next president. Follow events in Pakistan and Afghanistan, day by day. President Karzai has long been trying to consolidate central authority at the expense of regional warlords who ran vast chunks of the country as virtual kings. Among the most powerful: Ismail Khan, the former Afghan army officer who led an uprising against Soviet troops in Herat in 1979. After the Soviet pullout, he became a self-styled "Emir of the West." As mayor and then provincial public works chief under Mr. Khan, Mr. Yahya is remembered -- fondly by some Heratis -- for executing thieves and nailing dishonest merchants by their ears to lampposts. "He was brutal. But in this country you cannot govern if you are not brutal," said Alhaj Touryalai Ghaswi, vice-chairman of the Herat industrial union and the owner of several factories in the city. In an American-backed step to centralize power in 2004, President Karzai ousted Mr. Khan as Herat provincial governor. To retain his loyalty, President Karzai appointed Mr. Khan Afghanistan's minister of water and power. Once Mr. Khan left for Kabul, Mr. Yahya had to work with the new provincial authorities, who proved deeply unpopular as crime and corruption spiked, stifling Herat's post-Taliban economic boom. Criminal gangs, some allied with newly arrived police officials, went on a kidnapping spree, terrorizing prominent Heratis. "Most of the factories had to be closed and business activity shrank," said Mr. Ghaswi, the industrialist. "Business owners were afraid to move in the city because of all these abductions for ransom." Mr. Yahya also became a target of the Afghan government's anti-warlord drive that, with United Nations assistance, pressed smaller "illegal armed groups" to disarm. He refused, claiming not to have any weapons caches. So, in 2006, the new provincial government fired Mr. Yahya. Herat's governor at the time, Syed Hossein Anwari, said he had to make this decision because of Kabul's anti-warlord policy, and that he unsuccessfully tried to argue against Mr. Yahya's removal. The insurgent leader, he adds, was in those days "a decent, hard-working man with a good reputation because he never misused his office." Unlike Mr. Khan, the water and power minister, Mr. Yahya failed to secure another government job. He retreated to his ancestral stronghold in the Gozara district, a densely populated expanse of mudbrick villages that straddles the road between Herat's airport and the city itself. There, he quietly built up a militia that now numbers hundreds of men. "He was forced to go and take up arms," said Mr. Khan, who said he still maintains contacts with his former protg. According to area residents, Mr. Yahya hasn't enforced in Gozara the kind of harsh Islamic restrictions that are implemented by the Pashtun Taliban elsewhere in the country: Girls' schools remain open and youths in the villages are allowed to listen to music and watch television and pirated DVDs. But, like the Taliban -- whose ascent in the 1990s was welcomed by many Afghans tired of lawlessness -- Mr. Yahya has been ruthless in cracking down on crime. "People love him. He has punished all the thieves: now, not a single thief is left in our area," said shepherd Saif ud-Din as he tends his flock of sheep near the airport road in Gozara. "The only people who fear Ghulam Yahya are the criminals," adds local flower grower Noor Ahmad. It is hard to find anyone in Gozara -- and even in Herat -- willing to openly criticize Mr. Yahya. The insurgent levies taxes on peasants, and forbids them from paying land rent to the government or absentee landlords. Local youths are conscripted into his force. Some people who disparage Mr. Yahya in public have turned up dead. "Everyone is afraid of him. No one can speak out," said Mr. Taraki, the city's mayor. Initially, Mr. Yahya shied away from attacking Afghan troops or the Italian-led international forces in the area. But, last year, as he gave up hopes of rejoining the government, he repeatedly fired rockets at coalition bases and United Nations offices. He also launched lucrative kidnapping operations, holding anyone associated with foreign reconstruction efforts for ransom. An Indian contractor for international forces, seized by Mr. Yahya's men on the Herat airport road, died in captivity earlier this year. presence in Afghanistan cemented Mr. Yahya's alliance with the Pashtun Taliban. In an interview with Qatar's al Jazeera satellite TV network, Mr. Yahya boasted he has hosted Arab jihadis. Mr. Khan, the water and power minister, said Mr. Yahya turned to the Taliban because "everyone naturally needs support." The insurgent also appears to be getting some help from Iran, which used to cooperate with the West against the Taliban in the past. "The rockets that were launched against us [by Yahya] were Iranian-made," said Brig. Gen. Rosario Castellano, the Herat-based Italian commander of international forces in western Afghanistan. "The Iranians want a stable Afghanistan. But, at the same time, they also don't want Westerners to trample upon Afghan soil." Initially, Western and Afghan forces here abstained from a full-out assault against Mr. Yahya, in part because of concern about civilian casualties and the warlord's popularity. The current Herat provincial governor said he was stunned on his arrival late last year by how many people sang Mr. Yahya's praises. The governor, Yusuf Nuristani, said he wrote the rebel commander a letter in January, offering Mr. Yahya a full amnesty so that he can "come back and lead a good life." Mr. Yahya wrote back politely to turn down the offer, saying he has chosen the path of resistance because "your government doesn't have the power to throw out foreign troops from this country," Mr. Nuristani said during an interview in his Kabul apartment. On Feb. 16, coalition aircraft struck a compound 20 miles east of Herat, aiming to assassinate the warlord. In a press release at the time, the U.S. Forces in Afghanistan described Mr. Yahya as "a key insurgent commander ... infamous for brutal treatment against civilians and village elders" and said "up to 15 militants suspected of associating" with him were killed. But Mr. Yahya emerged unscathed. According to Afghan officials, though Mr. Yahya's car was in that location, most of the casualties belonged to a family of nomad shepherds, unrelated to the insurgency, who camped in a nearby tent. Since then, Mr. Yahya ordered ever more deadly attacks, including the Aug. 3 bombing that he claimed in central Herat, the worst strike against the city in years. Mr. Yahya's militia also prevented elections from taking place in most of Gozara and parts of the neighboring districts. "He's a criminal and a nuisance, and we want to get rid of him," Mr. Nuristani said. Last month, Italian and American troops launched a renewed offensive against Mr. Yahya's stronghold in Gozara. Another airstrike, in mid-August, once again missed the rebel commander but managed to kill one of his sons and his bodyguards. "We have dismantled his command and control center and are exercising constant pressure on him every day," said Gen. Castellano. "Every night, he must sleep in a different house." Yet, the fact that Mr. Yahya has survived is raising his prestige day by day, said Mr. Anwari, Herat's previous governor: "He's become a symbol and an example to others." Despite the recent bloodletting, Mr. Yahya can still be persuaded to come in from the cold if provided sufficient security guarantees, Mr. Khan said. "These people have no desire to be in complete opposition," the minister said in an interview in his palatial home in Herat. "There is no reason to fight all the time. There are other ways." According to Mr. Nuristani, the Afghan government's amnesty offer for Mr. Yahya remains on the table. So far, the insurgent's only response has been more rockets. (wsj)

Tuesday, April 16, 2024

Many tribal leaders now cooperating with Taliban in Afghanistan: military officials

IHC dismisses Bushra Bibi's plea seeking her shifting to Adiala Jail from Bani Gala

4:25 PM | April 16, 2024

Punjab CM visits Tehsil Headquarter Hospital Murree

3:25 PM | April 16, 2024

High-level Saudi delegation in Islamabad to hold meetings with Pakistani leadership

2:07 PM | April 16, 2024

Saudi foreign minister meets PM Shehbaz Sharif

1:17 PM | April 16, 2024

Decision to retaliate against Iran attacks rests with Israel, says Pentagon

1:05 PM | April 16, 2024

Political Reconciliation

April 16, 2024

Pricing Pressures

April 16, 2024

Western Hypocrisy

April 16, 2024

Policing Reforms

April 15, 2024

Storm Safety

April 15, 2024

Democratic harmony

April 16, 2024

Digital dilemma

April 16, 2024

Classroom crisis

April 16, 2024

Bridging gaps

April 16, 2024

Suicide awareness

April 15, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Advertisement

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024