Omar Samad

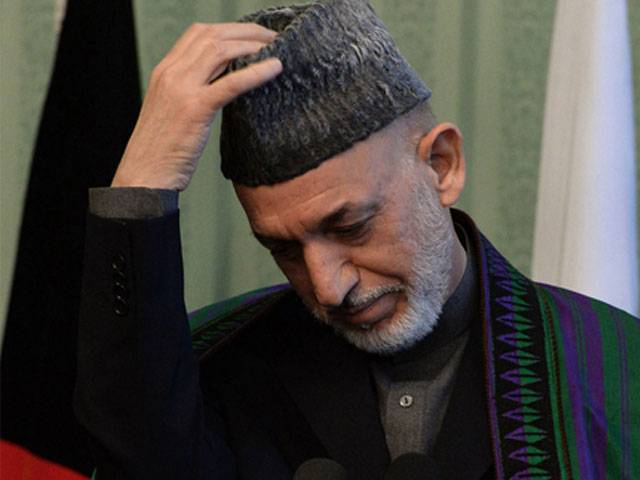

As Afghan President Hamid Karzai’s calculated and risky backtracking on the US-Afghan security agreement puts him on a collision course with most Afghans, the United States needs to demonstrate patience, take the Afghan public’s side and be tactful at a sensitive time in a highly volatile part of the world.

Observers describe Karzai’s actions as erratic, arrogant or impulsive. Others suggest that he be ignored or bypassed. To some, he seems to be displaying signs of exhaustion and irrationality. These views miscast Karzai’s motives and miss the point of his tactical political manoeuvring. He is engaging in canny clan-style brinksmanship.

Karzai’s instincts are shaped by his place in history. He is bargaining with the United States over a popular deal to allow up to 15,000 foreign troops to remain in Afghanistan after the formal end of combat operations in 2014. What lies at the heart of his aggressive posturing is the future of his family’s political and financial interests after his second term ends in 2014. That strategy has also been markedly shaped by 12 long and strenuous years of Machiavellian exploits, insecurity and frustration with his Western backers.

But, Afghans, wary of Karzai’s strategy and mindful of their destiny after 2014, are not in a mood to tolerate such antics so late in the game.

As international forces start ending their decade-long combat mission, foreign aid is shrinking considerably and Afghan security forces are tested by a nagging proxy war with the Taliban. Most Afghans are not only concerned about the future, but also about preserving the gains of the past 12 years in education, health, gender rights, media, entrepreneurship and even political freedoms.

For its part, Washington needs to be mindful of the stakes and not fall into Karzai’s trap. Arm-twisting is neither advised nor helpful at this stage as Afghans exert increasing pressure at home to make the President think twice about his responsibilities and priorities.

Anxieties are running high about Karzai’s last-minute wheeling-and-dealing and domestic and regional spoilers are sharpening their knives, hoping to see the back of the Americans and NATO departing South Central Asia for good next year if the agreement is not signed.

If it’s not signed and foreign troops must withdraw completely, the situation is ripe for terrorist outfits to create and fill a security vacuum. It will be hard for needy Afghan forces to defend against these groups without strong logistical and financial backing.

Training, advising and assisting the Afghan military and police forces over the next decade are essential elements for assuring long-term stability in the country and in fending off extremism and terrorism.

Failure to sign the bilateral security agreement will diminish international commitments, lower business confidence and exacerbate an already significant economic crunch in Afghanistan.

This does not mean that the Afghans, including Karzai, should blindly agree to Western terms. Karzai’s frustration to a large part stems from the inability - perhaps unwillingness - of Western forces to confront terrorists and extremists who are based in cross-border sanctuaries, with the exception of al Qaeda and, lately, outfits like the notorious Haqqani network.

The duality apparent in Islamabad between “good” and “bad” Taliban - those who are protected as strategic proxies and those they fight - has increased mistrust between Afghanistan and Pakistan, despite Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s recent day-long visit to Kabul.

Karzai is traveling to Iran and India in the next few days to have a heart-to-heart with regional heavyweights, some of whom - like Iran - are not too keen on seeing a continued American presence in the region.

Regional politics aside, the root cause of Karzai’s apparent insecurity lies in Afghan domestic politics. He wants to be kingmaker in next April’s presidential ballot, but also master of the larger endgame that might involve certain Taliban elements who, in his mind, would agree to a political deal.

The Taliban are also cashing in on Karzai’s gamble. In an unprecedented move, they issued a statement Monday praising his stance on the security agreement and refrained from calling him an “American puppet” for the first time.

Some have suggested the unlikely but not impossible scenario that Karzai may exploit the uncertainty to either delay elections or call for a state of emergency and take the country down an unsteady path. But Karzai has indicated that he would not interfere in the electoral process, knowing that would shatter his legacy, leave him stranded and cornered by all sides, with the exception of the armed militants.

Instead, it is more likely that Karzai’s latest risky gambit is more about style than substance; the subtle touch has never been his strong suit.

Whether these last resort overtures will open any doors to a just and peaceful settlement or help his side with the upcoming elections has yet to be determined, but at least he will be able to make a case that he did not toe the US line.

It is a major gamble that could backfire if US patience runs out or if other regional players increase their pressure through their proxies to put him off guard or disrupt elections. Complications could also arise if he is courted too warmly by the anti-security agreement circles inside and outside Afghanistan, at the detriment of the majority pro-agreement population.

The United States should spell out its own red lines but be flexible with demands that are not deal-breakers.

Afghans have given Hamid Karzai the benefit of doubt for many years, but their leader’s overall record has been patchy at best. People are openly advocating reform and are concerned about the rise of entrenched cliques backed by the President that appear intent on holding the country hostage and manipulating the elections in their favour.

The donor community needs to reassure the Afghan people in the face of these fears and extend the hand of friendship that has generated Afghan support for a continued international presence in the country. This can be best achieved by continuing to promote democratic governance, assist in the buildup of the Afghan national forces to help fight terrorism, protect women’s advances and invest in the young and entrepreneurial.

Omar Samad is senior Central Asia fellow at New America Foundation. He was the ambassador of Afghanistan to France (2009-2011) and to Canada (2004-2009) and spokesperson for the Foreign Ministry (2002-2004).–CNN

Friday, April 19, 2024

Be patient, the Afghans are fed up with Karzai

8:27 AM | April 19, 2024

8:09 AM | April 19, 2024

Pak economy improving, funds will be provided on request: IMF

9:57 PM | April 19, 2024

Minister advocates for IT growth with public-private collaboration

9:57 PM | April 19, 2024

Judges' letter: IHC seeks suggestions from all judges

9:55 PM | April 19, 2024

Formula 1 returns to China for Round 5

9:05 PM | April 19, 2024

Germany head coach Julian Nagelsmann extends contract till 2026 World Cup

9:00 PM | April 19, 2024

A Tense Neighbourhood

April 19, 2024

Dubai Underwater

April 19, 2024

X Debate Continues

April 19, 2024

Hepatitis Challenge

April 18, 2024

IMF Predictions

April 18, 2024

Kite tragedy

April 19, 2024

Discipline dilemma

April 19, 2024

Urgent plea

April 19, 2024

Justice denied

April 18, 2024

AI dilemmas unveiled

April 18, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Advertisement

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024