NEW DELHI : India marks three years since its last reported polio case on Monday, meaning it will soon be certified as having defeated the ancient scourge in a huge advance for global eradication efforts.

The milestone confirms one of India’s biggest public health success stories, achieving something once thought impossible, thanks to a massive and sustained vaccination programme.

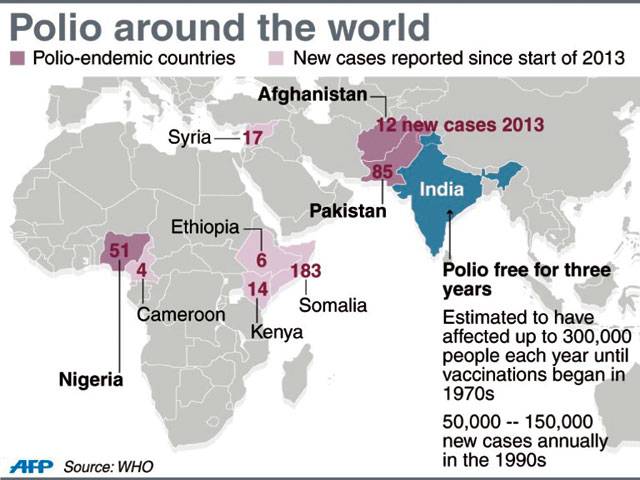

India’s health minister Ghulam Nabi Azad, along with global groups who have been working to eradicate the virus, hailed the three years as “a monumental milestone”. “In 2009 India accounted for over half of the global polio burden and today is the historic day when we have completed three years without a single case of wild polio,” the minister told reporters in the capital. With the number of cases in decline in Nigeria and Afghanistan, two of only three countries where polio is still endemic, world efforts to consign the crippling virus to history are making steady progress.

“In 2012, there were the fewest numbers of cases in endemic countries as ever before. So far in 2013 (records are still being checked), there were even less,” Hamid Jafari, global polio expert at the World Health Organisation told AFP.

“If the current trends of progress continue we could very easily see the end of polio in Afghanistan and Nigeria in 2014,” added Jafari, hailed as having played a crucial role in India’s victory.

Despite the success, isolated polio outbreaks in the Horn of Africa and war-wracked Syria emerged as new causes for concern in 2013.

To celebrate India’s success, the Rotary International charity, which has been a key donor, will illuminate the India Gate and Red Fort monuments in New Delhi with a message of congratulations.

India “proved to the world how to conquer this disease” despite its population density and sanitation problems, said Nicole Deutsch, head of polio operations for UN children’s arm UNICEF in India.

Countries are certified by the WHO as being polio-free if they go 12 months without a case, and are then said to have eradicated it after a period of three years without new infections.

India will likely receive this endorsement only in March, which will trigger more exuberant celebrations than on Monday.

There also remain reasons for caution, with the virus still considered endemic in Pakistan, where vaccinators are being killed by the Taliban which views them as possible spies.

Hopes of progress were given a boost last month when cricketer-turned-politician Imran Khan pledged to personally spearhead vaccination efforts in the troubled northwest of the country.

In India, the wretched sight of crippled street hawkers or beggars on wheeled trolleys will also remain as a legacy of the country’s time as an epicentre of the disease.

In the absence of any official data, most experts agree there are several million survivors left with withered legs or twisted spines who face discrimination and often live on the very margins of Indian society.

The country’s success was built on a huge vaccination programme that began in the mid-1990s with the backing of the central government and a coalition of charities, private donors, and UN agencies.

An army of more than two million vaccinators, backed by local religious and community leaders, canvassed villages, slums, train stations and public gatherings in even the most remote parts of the country.

The country reported 150,000 cases of paralytic polio in 1985, and it still accounted for half of all cases globally in 2009, with 741 infections that led to paralysis.

In 2010, the number of victims fell to double figures before the last case on January 13, 2011, when an 18-month-old girl in a Kolkata slum was found to have contracted it.

The girl, Rukshar Khatoon, is now attending school and leads a “normal life”, although she still suffers pain in her right leg from the disease, doctors and her parents told AFP.

“She can now stand on her feet and walk, but can’t run,” her father Abdul Saha said. “When her friends play, she remains a spectator.”

Saha, a father of four, conceded he had taken his son to get immunised but not two of his daughters. “It was a grave mistake,” he said.

Jafari from the WHO highlighted the immense knock-on benefits for India, which is still afflicted by other preventable diseases, widespread malnutrition and poor sanitation.

“India has now set other important public health goals as a result of the confidence that the country has got from the successful eradication of polio,” he said, citing a new measles eradication goal.

Friday, April 19, 2024

India defeats polio, global eradication efforts advance

Caption: India defeats polio, global eradication efforts advance

8:27 AM | April 19, 2024

8:09 AM | April 19, 2024

Pak economy improving, funds will be provided on request: IMF

9:57 PM | April 19, 2024

Minister advocates for IT growth with public-private collaboration

9:57 PM | April 19, 2024

Judges' letter: IHC seeks suggestions from all judges

9:55 PM | April 19, 2024

Formula 1 returns to China for Round 5

9:05 PM | April 19, 2024

Germany head coach Julian Nagelsmann extends contract till 2026 World Cup

9:00 PM | April 19, 2024

A Tense Neighbourhood

April 19, 2024

Dubai Underwater

April 19, 2024

X Debate Continues

April 19, 2024

Hepatitis Challenge

April 18, 2024

IMF Predictions

April 18, 2024

Kite tragedy

April 19, 2024

Discipline dilemma

April 19, 2024

Urgent plea

April 19, 2024

Justice denied

April 18, 2024

AI dilemmas unveiled

April 18, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Advertisement

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024