David Pilling

Human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe — HG Wells.

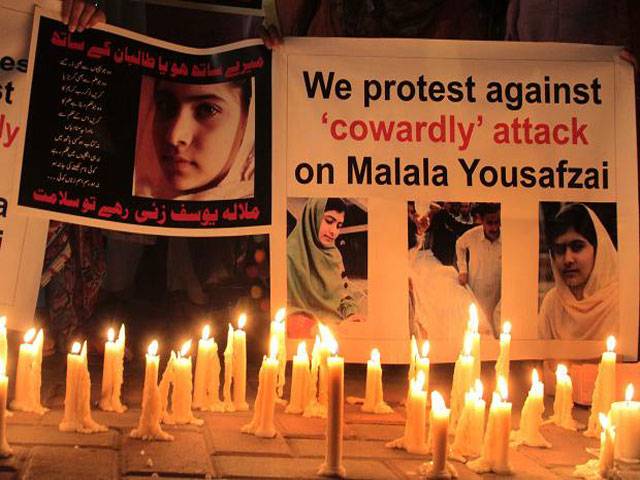

Sick and tired of the supposedly ‘negative propaganda’ being pedalled against hardline Muslims by a 14-year-old girl, members of the Pakistani Taliban decided to do something about it. They shot her in the head. Malala Yousufzai’s ‘crime’ was to advocate girls’ education. That, and her admiration for US President Barack Obama, led the Taliban’s chief spokesman to describe her as “a symbol of the infidels and of obscenity”. His organisation has in the past busied itself blowing up dozens of girls’ schools and beheading ideological opponents, presumably in the cause of piety and decency.

The attack on Malala, who has now been flown to Britain for emergency treatment, has galvanised moderate opinion in Pakistan. Mass rallies have been held to pray for her recovery and many of Pakistan’s leading religious groups have joined in condemning the attack. The outpouring is reminiscent of the national shock that greeted images of Taliban flogging women in the Swat valley three years ago and support for a subsequent military assault against extremists.

Before she was flown to the UK, General Ashfaq Parvaiz Kayani, Chief of the Army Staff, visited Malala in the Peshawar hospital where she was being treated. General Kayani, who called the attack “a heinous act of terrorism”, said: “Islam guarantees each individual — male or female — equal and inalienable rights to life, property and human dignity.” Given the circumstances, he would have done well to add “education”.

It has taken the bravery and eloquence of a 14-year-old girl to highlight a crucial development issue: Female education. A 2004 study on girls’ education, titled A Scorecard on Gender Equality and Girls’ Education in Asia 1990-2000, found that Pakistan ranked at the bottom among 17 Asian countries. The study measured four criteria, including girls’ enrolment and five-year “survival” rates at primary school. Of a possible rating of 100, achieved by Japan, South Korea and Singapore, Pakistan scored just 20. That put it below Laos, at 26, and Myanmar, at 34.

The study had some interesting conclusions. First, Asia is divided into two fairly distinct groups, with one half doing well, the other badly, and not much in between. Among the better performers, China, Thailand and Indonesia are grouped with the advanced countries already mentioned. India is firmly in the lower half. It has a score of 41 compared with 89 in China.

There is a correlation between girls’ education and national wealth, but some poorer countries — notably China and Sri Lanka — do much better than their per capita income would predict. Countries with strong basic education often go on to do well economically. Japan’s remarkable success after the Meiji Restoration drew much of its vigour from an educational push that made it almost fully literate by 1910.

Countries with a history of communism or central planning tend to do better than those without. China, Vietnam and the central Asian republics of the former Soviet Union do well. The correlation is not perfect: Communist Laos fares abysmally. Countries that have experienced a recent conflict do badly, though they can buck the trend. Vietnam does well and Sri Lanka, whose 30-year civil war only recently ended, does even better, with a score of 94.

Does female education matter? Study after study shows that it does. Female literacy improves health and enables women to assert their legal rights. A recent study titled titled Literacy and Mothering: How Women’s Schooling Changes the Lives of the World’s Children in Mexico, Nepal, Venezuela and Zambia found that literate women are far more likely to understand and act on health messages. Education also affects fertility rates. Literate women tend to marry later and have smaller families.

There can be marked differences within countries. Amartya Sen, Nobel laureate economist, says that in the Indian state of Kerala, where girls generally go to school, women have, on an average, 1.7 children against more than four in many other parts of India.

There appears to be a correlation, too, between educated women and a decrease in sex-selective abortions. Putting more girls in school is the single best remedy to the tragedy of millions of ‘missing’ women, though the link breaks down in China where the one-child policy has distorted the picture.

Professor Sen also warns against what he calls “illiberal and intolerant education”. He argues that religious schools — including madrassas, the Islamic schools that flourish in Pakistan — often spring up to fill a vacuum left by the lack of state education. Schools in the Arab world, he points out, have a rich tradition to draw upon beyond religion, including “the great secular accomplishments in mathematics, science and literature which are part and parcel of Arab history”.

Parents and children in poor countries understand the intrinsic value of learning and the tangible benefits that can follow. Anyone who has seen children trekking miles to school along dirt roads knows it, too. That was — and is — Malala’s message. More than her hero Obama, hers is a conviction worthy of the Nobel Peace prize. –Gulf News

Thursday, April 18, 2024

Malala for Nobel Peace Prize: Why not?

Mehwish Hayat says she would like to work with Aamir Khan

9:59 PM | April 18, 2024

'That'll be awesome,' Rohit Sharma on idea of Pakistan vs India Test series

9:17 PM | April 18, 2024

Turkiye commends Pakistan's efforts in fostering regional peace

9:03 PM | April 18, 2024

CM Maryam's security squad hits biker to death in Narowal

9:02 PM | April 18, 2024

Hafiz Naeemur Rehman sworn in as new emir of Jamaat-e-Islami

8:54 PM | April 18, 2024

Hepatitis Challenge

April 18, 2024

IMF Predictions

April 18, 2024

Wheat War

April 18, 2024

Rail Revival

April 17, 2024

Addressing Climate Change

April 17, 2024

Justice denied

April 18, 2024

AI dilemmas unveiled

April 18, 2024

Tax tangle

April 18, 2024

Workforce inequality

April 17, 2024

New partnerships

April 17, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Advertisement

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024