Andreas Ulrich

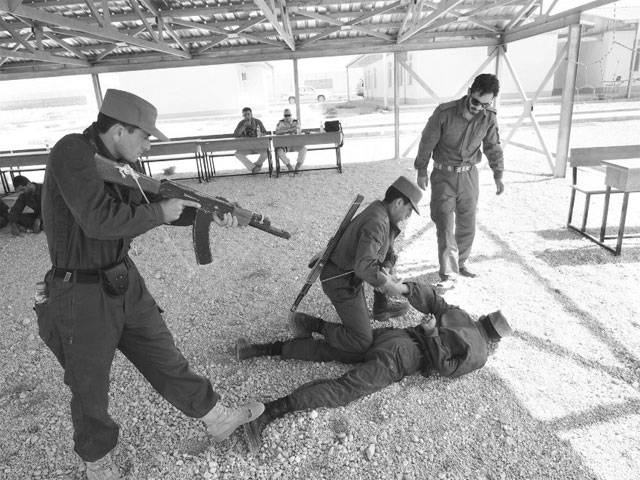

The Afghan national sport is called buzkashi. It’s a game in which horsemen battle over a goat carcass. There are no established teams.During a match, the competitors forge brief, continuously shifting alliances. They only work together until they have gained a short-term advantage. The game can last for hours, even days. The winner is the rider who manages to carry the carcass to the goal. Buzkashi is a mirror of Afghan society. By contrast, the German police officers who train local recruits in Afghanistan have brought soccer balls and nets to their base in Mazar-e-Sharif. Football is all about teamwork and team spirit. The goal is to form a team and achieve an objective together. In a corner of the training center, on a patch of parched earth, there is now a soccer field where the next generation of Afghan police officers is learning the game. “What we want to achieve with the recruits is a change in mentality,” says a German instructor. More team spirit, a better sense of community, more loyalty. More soccer, less buzkashi. Over the past 10 years, Germany has instructed some 56,000 Afghan police officers at four training centers in the region. The training is part of Germany’s responsibility as a member of NATO, and so far the project has cost some €380 million ($503 million). As many as 200 German police officers are regularly stationed in Afghanistan, most of them in Mazar-e-Sharif. But anyone who accompanies the German security aid workers for a few days is bound to doubt the mission’s effectiveness after observing the mood among the officers and reading between the lines of official statements. Even now, when Western security forces have entered their 11th year of training, the police in Afghanistan don’t stand for public order and security — but rather for helplessness, arbitrariness and corruption. A Prime Target “The mission is neither effective nor sustainable,” says Josef Scheuring, chairman of the Germany’s largest police union, the GdP, adding that it endangers the lives of the German police officers. “We should withdraw from Afghanistan as quickly as possible,” urges Scheuring. Nevertheless, police officers continue to work in the region, usually for a year. They are attracted by overseas bonuses of up to €200 per day. Alex, 32, a mid-level police officer from the northeastern German town of Ueckermünde, is one of them. He is due to meet with Ayatullah at the Regional Police Training Center (RPTC) in Mazar-e-Sharif late in the afternoon. The next day, the 22-year-old low-ranking officer in the Afghan national police force will show class 6.2 how a road checkpoint works. “Checkpoints are crucial,” says Alex, adding that “they have a high death rate.” This makes it important to teach “survival skills,” as he puts it. Of all the uniformed officials in Afghanistan, police officers are at the highest risk. Secluded from the outside world, many of them spend weeks at such checkpoints and are charged with representing the state. They are a symbol of the new Afghanistan, which is massively supported by the West — and thus a prime target for insurgents. There are currently some 150,000 police officers in Afghanistan. Since 2002, when various Western nations launched training programs, it’s estimated that nearly 10,000 police officers have been killed — and some 15 percent desert the force every year. Alex plans the next day with Ayatullah. “We’ll meet at 7:50 a.m. in front of the armory, and by 8:20 a.m. the checkpoint will be set up. Is that enough time?” asks Alex. “No problem,” says Ayatullah. “We need a patrol car and a civilian car, plus three boxes as barriers. Ideally, by this evening already. Is that okay?” Ayatullah nods.“Okay, I’ll see you tomorrow,” says Alex. A Critical Phase The ambitious project of developing an Afghan police force, which was to operate at least according to the basic principles of its German counterpart, began 10 years ago and involved three phases. Phase 1, training recruits, was completed long ago. Phase 2, instructing the police officers in practical operations on location, was abandoned last year. German police officers — at the time still under the protection of German soldiers — drove through the country for hours to call on various police stations. Since they had to be back before sundown due to security concerns, there often remained very little time for training. Phase 3 is currently underway: Afghan police officers train Afghan recruits while the Germans monitor them. They correct mistakes and give suggestions. Based on the methodology and didactics of the German police school, it is hoped that the Afghans can train uneducated men to become good officers in just eight weeks. Like all German police officers in Mazar-e-Sharif, Alex is living at Camp Marmal, the headquarters of the coalition troops in northern Afghanistan. The ISAF military base is one of the safest places in the country — a well-equipped artificial world with shops, cafeterias, gyms and pool tables. Private security guards stand at the gates, while soldiers patrol outside the compound. A zeppelin floats in the sky, jam-packed with cameras and surveillance electronics. The German police officers are not allowed to leave the camp. They used to accept invitations to eat meals with locals, were allowed to move about freely and had opportunities to get to know the country. Today, that would be unthinkable. The upcoming ISAF withdrawal has made the security situation extremely precarious. Lieutenant General Rainer Glatz, the commander of all German military operations abroad, says that the mission in Afghanistan has reached a “critical phase.” Glatz says the Afghan army and police will soon undergo a litmus test to see whether and how they can ensure security without outside help. –Spiegel