She’s smart, she’s beautiful, she has a respectable job, a loving family, but she’s miserable, and so is her family. She’s in her 30s and she’s unmarried.

In Pakistan, marriage is not just about having someone to share your life with; it’s not just about wanting children. For a woman, it’s about being chosen. And “their” choice takes precedence over her own choices, hence she struggles to become and remain someone “they” would choose until it happens, and more often than not even after it happens just to make sure it stays that way.

In a patriarchal society where a Pakistani woman enjoys reverence and care, she is also judged harshly for wanting something more out of life. She is responsible for the honour of her family, her husband. Under the guise of security and protection, she’s constantly scrutinized for what she chooses to wear or say, how religious she appears to be or how she lives her life. Even though she has now learnt and knows about places in the world she would love to visit, she will not be allowed to travel alone. Even though she now knows and has learnt that it is possible for a woman to enjoy a successful career and live independently, she will not be able to choose that as a lifestyle. With all this, she will also gradually learn to judge other women, who after having had a similar exposure choose to make things happen, who travel alone and live independently, and don’t apologize for their choices.

Learning is a constant and a continuous process. We as human beings have been learning for centuries from our environment on a conscious and subconscious, cellular and organismic level. Our experiences and the stimuli we are exposed to shape our minds and our personalities.

Today wherever we might be living in the world we are exposed to different cultures, different lifestyles. We’re constantly fed ideas about what an ideal life should be. As a country we’re in a phase of transition where our old beliefs, customs and traditions are gradually being replaced by modern thoughts and ideas, by universal and basic human values. We might think that with all this exposure we would have our priorities aligned better, we would have a better understanding of our rights, would be better able to tell right from wrong; to differentiate between good and bad. Probably true, but at the same time we’re learning that knowledge doesn’t necessarily lead to practice.

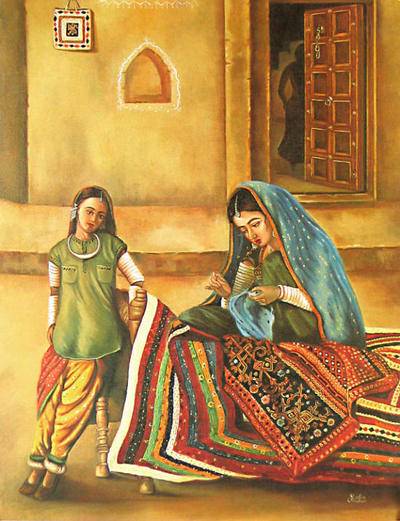

Before she is born, the entire course of a typical Pakistani woman’s life, her character and personality has been defined for her. She will learn to dress properly, she will learn to cook, clean and be a good homemaker, she will get some education but usually just enough to be chosen by an appropriate suitor, she will get married, she will have children and make sure her daughters grow up to be like her so they too can be among the chosen women of the society and have a similar life.

But is it because we know it works or it is because we feel we are captives of a system and are afraid to be alone in it? Hence this is how it is; this is how it must be and must stay and if it doesn’t, it says something about you.

Most (not all) women who deviate from this plan that has been outlined for them and has been meticulously followed by women in their families for generations, have to suffer as they tread a new and unknown path. These women who question what must never be questioned become a cause of stress for their parents and somehow a threat to the society. They are judged and criticized harshly. They’re harassed until they crack under pressure, give in and join the rest of them.

For today’s Pakistani woman it’s a constant struggle to strike the perfect balance between choosing who she wants to be and becoming someone others would choose and pick out of a lot (or simply accept as one of their own). Most of the time, she will tilt towards the latter, because the consequences of the former might be too cumbersome and very few women are equipped to deal with them. Most of them are then forced to lead a dual life.

However, I personally know a few who have done it and who have made it, but they put their foot down only after having their hopes dashed, their hearts broken or their prides hurt. It was not their first choice. I’m not holding that against them, I just thought it’s worth mentioning.

But what I wonder about is the fate of those women who are inadvertently thrown out of this cycle.

What about those who do everything they’re told they’re supposed to do, but are still not “chosen” and never get married (like the one I described at the beginning of the article who inspired this whole piece)?

What about those who do get married, but end up getting divorced, i.e. the ones who are chosen and then “rejected”? (It’s worse for those who walk out on their husbands.)

We all know what happens to these “unchosen”, “rejected” and “misguided” ones.

It’s every person’s right to decide and to choose how they live their life, and no one should have to fear abandonment or rejection based on very personal and harmless choices about life and career. Nor should a person’s worth be defined by anything other than the values and principles they live by.

I’m not a feminist. I’m not trying to start some kind of an upheaval, nor am I suggesting that long-standing traditions be expunged. If a system persists to exist, it’s because it works, or has worked so far. But the dilemma that today’s Pakistani woman faces deserves some attention and needs to be understood. By making approximately 52% of our population part of a line-up, waiting to be chosen or accepted, living in constant fear of becoming a social pariah, we reduce them to chattel. We help no one and just propagate a system the purpose of which is nothing more than self-sustenance.