When I got my posting in Lahore in 2011, I had a fair idea that this would in most probability mark the end of my long army career in uniform. Lahore happened to be my hometown as well and I did have an ancestral house there. But this was quite far off from the Cantonment, besides being occupied by my youngest brother; besides, over the years we had accumulated enormous household stuff (this included a pair of German Shepherds, a cocker spaniel, a lab and a pair of parrots) all of these could not be accommodated in an already furnished house. Lahore being a big cantonment always witnessed heavy influx of officers. The official accommodation therefore remained an anathema. An incoming officer invariably had to wait for, depending on his personal luck from three to six months. When I arrived at Lahore the situation was no different. However, seeing my predicament the Quartermaster Staff Officer indicated to me a house near sadder Bazaar which had been vacant since long owing to its old debilitating and crumbling structure. He referred it as the ‘Step House’ something vividly explaining the story behind. It was a frowning sight when I and my wife visited the old grotesque structure. Without giving a second thought we out rightly rejected it. It was a hateful sight of a true Bhoot Bangla. As official accommodation was nowhere in sight, we rented a house in the nearby colony of retired officers. This was a newly built house albeit small and cagey with hardly any front lawn. No sooner than later our dogs and birds started feeling the suffocation. Besides, the rent was four times higher to what we were receiving as official house allowance. After four months I contacted the Headquarters only to learn that there was still no let up. The only thing available was the ‘Step House.’

On assurance by the concerned officer of some quick fixes and repairs we decided to take the house. Fifteen days later we moved our stock and barrel into that insalubrious structure.

Built on nearly an acre it was a single story quite placidly simple with a large front veranda. The main entrance led to a large central room on both sides of which were four bedrooms and a small dining room with wide windows allowing the satiated view of the front and side lawns. On one side of the building there was a small round patch bearing the number 1890 signifying the year of its construction. A vast unkempt lawn sporadically interspersed with all kinds of fruit trees. These old trees canopied the building and the front verandah, which were further masked by the thick foliage of the grape wine. In the backyard, besides the kitchen garden—which presented the spectacle of a thicket—there laid a line of ten servant quarters all in partial ruins. In the other corner, there was a small hutment consisting of two huts with a horse feeding trough outside. This was the stable. This explained as to why the house did not have a car shed. There was also a spacious shed for raising chicken with remnants of thick ripped-off wire gauze still dangling helter skelter. This was however revamped and soon it was fluttering with domestic chickens. Soon the vegetable garden also started to yield its produce. Amazingly the actual kitchen was detached from the main building in a corner of the backyard. I later found out that in those days the kitchen used to be detached from the main house. In later years, one of the four bedrooms was converted into a kitchen. The house was a delight for the pets that were seen rejuvenated in that vast, shady abode. The dogs rejoiced with the proverbial victory dances under the trees, till their shenanigans turned into a daily family entertainment for us. To us, it was an acquired taste. Where the bungalow posed a certain kind of discomfort, lacking in modern day amenities of standard contemporary houses, it enabled us to experience a living so different from the one that would have been in a standard house. It satiated our yearning for a simpler life, this simplicity however got elevated to something unique in its own way for us. The homegrown vegetables, chicken, eggs and a variety of animals helped brought us closer to nature. The verandah was a luxury for an evening cup of tea and snacks with the family.

My octogenarian aunt, a professor and a renowned writer by profession who despised visiting any of her nephews and nieces, developed a special liking for the house. She was a frequent visitor and would spend her weekends with us. According to her the house reminded her of yester years at their pre partition house in Lukhnow. It was she who prodded me to explore more about the house “Iss Ghar mein zamanay band hein” (this house encapsulates eras) she would often say. Living there we would imagine as to how many British families must have had planted their footsteps in the house: Sahebs, Mem sahebs, Chota sahebs (children) and their entourage of servants. During the same time my interest in exploring the origin of these Bungalows (including the Dak Bungalows located at remote and far flung, often inaccessible places) all over the subcontinent grew manifolds. My quest for an in depth exploration of these, instilled into me a renewed interest in the tales and literature of ‘The Raj’ (for it is the British Raj that we owe these Bungalows to), which I nurture till date.

History has it that the word ‘Bungalow’ came from the word Bungla, meaning of or from Bengal. The purpose of these dwellings was to provide British officials, both civil and army, a safe and comfortable lodging. In addition to the ones meant for permanent living, Dak Bunglas or Bungalows (word dak is urdu for post) were built by the British Public Works to facilitate postal officers relay the mail in stages. It is staggering to note that while the ones built for permanent dwellings in big towns and cities, the usual nomenclature changed from ‘Bungla’ to ‘Bungalow’ sounding aristocratic, while the remotely located temporary ones are normally referred to as Dak Bungla. From the foothills of the Himalayas to the edge of Kerala, these bungalows were strikingly uniform with minor vernacular variations depending on what material was locally available and the pattern of prevailing weather conditions; for example, thatched roofs in places with more monsoon and flat roofs in Punjab, Rajhastan etc. The origin of its construction lies with the British military engineers in the eighteenth century to design a standardized and permanent dwelling based on indigenous domestic structures for the East India Company. These Bungalows were initially Kuchcha that is with mud wall and thatched roofs, but in later times reinforced with brick or mortar. The interior of the bungalow, however, kept very much to one pattern: large, well-ventilated rooms, high ceilings and plain white-washed walls. There was nearly always a wide verandah running round the outside of the house, leading through the front into a large living room, with bedroom suites on either side. The living room led through into a dining room. The kitchen stood back by itself behind the bungalow near the servant quarters.

A Bungalow in Abbottabad

These bungalows, usually built on large, sprawling compounds where birds could be raised and vegetables grown to make them self-sustained in the absence of regular provisions. According to many published sources, in 1880s, a well-to-do European family establishment in India would need twenty seven servants and around fourteen in case of a bachelor household. The bachelors’ accommodation where four or five bachelors could share a house was however completely different in construction and was known as a ‘Chummery.’ Since these servants were often accompanied by their wives and children and in some cases even their parents, the actual number could swell up to sixty. These included a number of fringe occupations such as Palkee-wallah (palanquin bearer), Punkah-coolie (fan puller), Ayah (the nanny), Maashqui (water bearer), Mehter (sweeper), Maali (gardner), Mushshalchi (torch bearer), Khitmutgar (attendant usually known as Khit), Chawkidar (nightwatchman) and so on. However, the core of the household remained the same. Its key figures were the Khane Saman or Baawarchi (the cook) and the Butler. In the 1930s, with the coming of electricity and motor car coupled with the soaring cost of living, this number got reduced to seven—this cost the average employer about two hundred rupees a month.

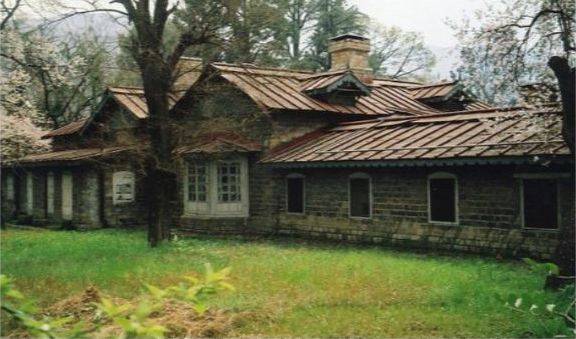

A typical bungalow in northern area

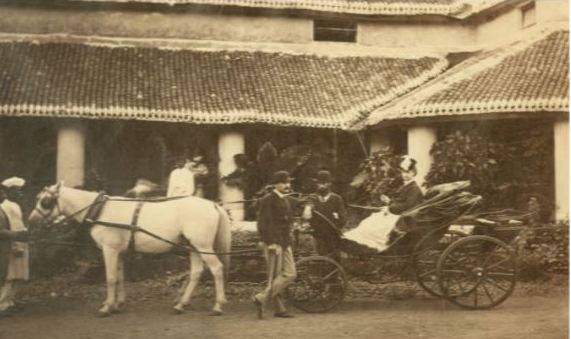

A typical bungalow mostly found in Punjab

In the 19th and early 20th centuries as the official administrative machinery expanded and more complex system put in place, more and more number of English officials were required to travel to remote Indian hinterland, staying in camps and tents, mostly in the midst of very hostile environment. These officials had to travel with their servants and camp equipment. The difficulties would compound in the case of natural calamities such as monsoon and floods, not to mention ending up with one of the innumerable bands of ever-active thugs and bandits infesting the ‘badlands’. The Dak Bungla in such conditions was a luxurious haven away from home and served well as a temporary home, an office and perhaps one’s last defense against insurgents and wild animals. Lt Col JK Stanford, a British Indian Civil servant, in his memoirs of India, wrote that a touring official was given seven rupees and eight annas as a nightly travelling allowance that paid for the horse’s feed, firewood, eggs, chicken and so on.

John Frederick Foster, Assistant Surgeon, Her Majesty’s 36th Foot, in his diary Three Months of My Life, (a wonderful account of his journey from Peshawar to Kashmir via Murree in 1868, published posthumously in 1873) narrated experiences of his sojourns in these Dak Bungalows. The bungalows were adequately furnished and were invariably managed by a cook cum manager, known as Khan e saman—a man as old and decrepit as the bungalow itself. Since all of these bungalows were adequate in rich supplies of their self-raised chicken, this bird customarily became the mainstay of each meal. A typical scenario witnessed in any dak bungalow of each time that a gora sahib arrived in his dak gaari (dak carriage) was narrated by Foster:

Oh English readers, you who have never wandered far from your native shores and who esteem chickens a luxury to put on your supper table at your festive gatherings, come to India and surfeet on your dainties, you will see it calmly collecting its daily food unsuspicious of danger, then comes the rush and loud clacking as it flies pursued by the ferocious native (the khan e saman wielding a knife to catch the escaping chicken) ending with cries of despair and the fluttering and hoarse gurgle of its death throes, in half an hour the murghi will be placed before you hot and temping to the eyes but hard as nails to the touch; they are cheap in this part of the world… Chicken for breakfast, Chicken for dinner, Chicken yesterday, Chicken tomorrow, toujours Chicken, sometimes curried, sometimes roasted, torn asunder and made into soup, stew or cutlets or with extended wing forming the elegant spatchcock, it is still chicken (63-4).

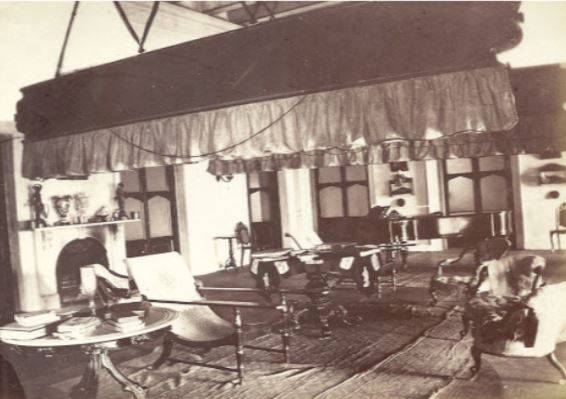

Glimpse of a typical dining room

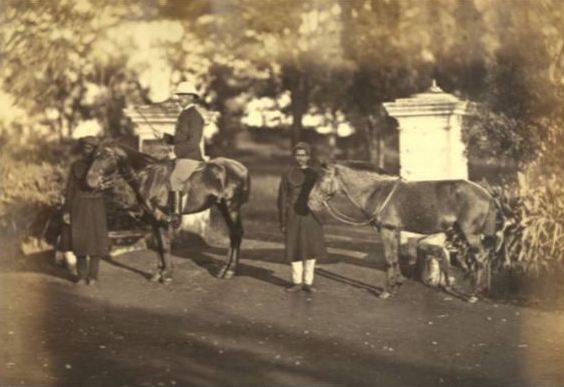

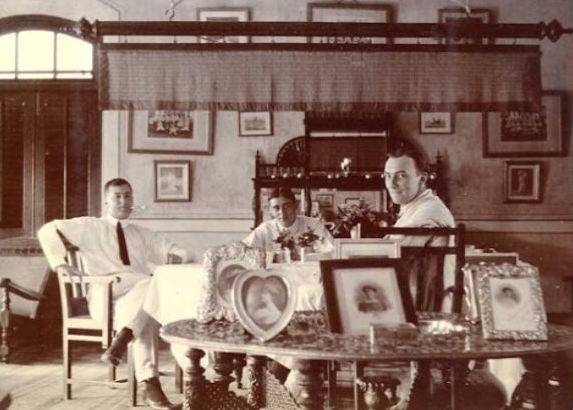

A moment to relax and gossip

Coming back to our own bungalow, during the course of my three-years stay I was amply offered better accommodations by the Army, all of which were purposefully put down by me and my family. One of our dogs, the Cocker Spaniel, died during our last months in the house and was buried with complete last rites under a thriving bougainvillea shrubbery. My youngest daughter espoused the idea of the dog’s grave being under this blossoming creeper, which would happen to perennially shower its tiny flowers on the late dog’s grave.

Six months prior to my retirement, I was served with a letter notifying me to vacate the house, as it was deemed dangerous for living. The letter reasoned that the house was too old and weak to accommodate families and that it needed to be demolished. In its place, a compound for multiple number of married-officers’ accommodation was planned to be constructed soon. Despite the fact that we were offered a new house in the near vicinity, my family was not willing to move out from this house—a house that sheltered us for three unforgettable years and that nourished our beings with its incomparable warmth. Later I took up a case with the authorities to delay the process, but to my displeasure this was refused as the construction plan had already been scheduled, and had to take place within the stipulated timeframe. Ultimately, we had no choice but to vacate and shift into the new house that was offered to us, which happened to be right across the road. Soon after we had shifted, the demolition machinery arrived at the location and we were informed by our servant that they were about to take the old house down. Though not unexpected, the news hit me and my family tumultuously and we went outside to pay a last goodbye to the bungalow that had housed us for three years.

The huge excavator struck the front wall of the house with its massive claw, and with a spur the house, rejected by many and embraced by many, and that had warmly nurtured my family for three years, came down with a roar. They say when someone very close to you dies, a part of you dies with him. That night, I felt as if a part of us—all the beings that had lived there in different eras, who had spread smiles and shared food and prayed in their own ways—died too.