About the Postcolonial Feminist Realm:

In Under the Western Eyes, Chandra Talpade Mohanty criticizes homogeneous perspectives and presuppositions in some of the Western feminist texts that focus on women in the third world. More specifically, the author anchors her accounts of Western feminism in a select group of texts produced by Fran Hosken, Maria Cutrufelli, Juliette Minces, Beverly Lindsay, and Patricia Jeffery published by Zed Press in what is entitled the Third World Series. According to Mohanty, these writers draw attention to the codification of scholarly writings that discursively colonize and ghettoize non-Western, “Third World” women as the collective Other. She argues that the universal categorization of a large group of women in non-Western countries is mostly done through constructed monolithic terms and classifications.

Chandra Talpade Mohanty in her article, Under Western Eyes, states:

Universal images of ‘the third-world woman’ (the veiled woman, chaste virgin, etc.), images constructed from adding the ‘third-world difference’ to ‘sexual difference’, are predicated on (and hence obviously bring into sharper focus) assumptions about western women as secular, liberated and having control over their own lives. (61)

In global perspective, all notions of the selfhood have been masculinized, and in the post-colonial world this notion has been used by the western feminists to collectively create a monolith of Third World women labelling them with their own definitions i.e. all Third World women are weak, demure and not capable of exercising their agency and/or fending for themselves. Mohanty’s views highlight that women in the eastern world are categorized as colossal terms, these terms are made the standards by which the western feminists define women in the Third World as lowbrow and monolithically subjugated, for instance, the western feminists feel that women in the Third World countries all have political, social and cultural linkages; they all have the same views and the same stance on various political restructurings and overhauls in the world. Mohanty argues that contrary to how the western feminists define them as, all women in the East are different in terms of their struggles, their political and social bearings and are generally different from one another because they all come from diverse backgrounds, have been raised in different households and have had different experiential realities altogether, which is why there cannot be a blanket term to define them all as “discriminated against”, “downtrodden”, “submissive”, “weak” or “victims”.

Mohanty says in Under Western Eyes:

I am not objecting to the use of universal groupings for descriptive purposes. Women from the continent of Africa can be descriptively characterized as “women of Africa,” it is when “women of Africa” becomes a homogeneous sociological grouping characterized by common dependencies or powerlessness that problems arise—we say too little and too much at that same time.

Fawzia Afzaal Khan grew up in Pakistan, attended a Roman Catholic school and then Kinnaird College for Women before leaving for the US for her Ph.D. degree where she later accepted a job. A Professor at Montclair State University specializing in feminist and postcolonial studies, Khan is also a poet and an activist for Muslim women’s movements.

The narrative style of the book, as Carole Stone asserts in the Foreword, is more multifaceted than a memoir. A poet herself, Afzal-Khan ponders over her own resourceful and artistic position, with her orientation based on other American memoir writers, focusing on the style as well as the content. The memoir also takes several practices in terms of its literary forms, ranging from verses, parodies, stream of consciousness narratives, along with the confessional tone of an autobiography.

Khan’s memoir is an eye-opener for the young generation of Pakistan that swivels an eye over the absmal, assymetrical society that comprises binary extreme of factions, fanatical extremes and westernized liberals. It talks about how Pakistan took a rollercoaster ride from Socialism to Islamization, and how this perilous ride affected the very roots of the social and ideological fabric of the country; how from the departure of the erstwhile practice of drawing-room discussions to street politics and then to a complete dictatorial/dogmatic system, things changed consequentially. Critic Swaralipi Nandi says about Khan’s work:

Afzal-Khan recounts numerous instances of paradoxes that characterized the Pakistani middle class whereby Westernized lifestyles coexisted with ‘fanatical extremism,’ and liberalism for women’s education and homosexuality contradicted the racism people showed for the East Pakistanis. In terms of women’s position, however, the society remained unanimously patriarchal in restricting them primarily to the domestic role. (44)

Khan’s memoir establishes that women in the Third World countries all have different experiential realities and that their individual struggles, during and after Zia’s era, are empirical evidences against the monolithic terms used by the Western feminists to define their identities and their existence.

Introduction to the Lahore with Love: Growing up with Girlfriends Pakistani Style

Fawzia Afzaal Khan’s memoir Lahore with Love: Growing up with Girlfriends Pakistani Style is an amalgamation of the personal and the political. Khan makes it deeply effective to the ears that one’s personality cannot be divorced from the political, social, religious and cultural ambit that he is exposed to during the formative as well as the mature years of his life. Khan’s memoir is a brilliant representation of how unrecognizable the pre-Zia Pakistan had become to the Post-Zia one; so much so, that the very consequential Zia’s regime had rendered it impossible for the middle-class, secular mind to think modestly about a society based on the foundations and principles of gender equality; about women issues and matters involving their political and social rights; and even his own faith. Khan’s memoir encompasses an explanation of personal and political experiences that culminate into reflecting how the society had disintegrated into categories of binary extremes during the Zia era, the aftereffects of which continue to cling to the social and cultural fabric of this country till date. It carries out an exegesis into the political events that affected social and cultural ideology of the people inhabiting Pakistan during and after the Zia era; the individual pursuits and collective struggles of women as mentioned in the novel (also validated by contemporary artists and freelance columnists); as well as an exploration of gender roles as described in the novel.

Political Events Affecting Social and Cultural Ideology

Any society is a system that essentially encompasses localized trends of age-old values and a certain pattern of behavior exhibited over a course of time by individuals that are a part of that society. Individuals of a particular society behave and react to various issues in a certain way because they are socially conditioned to respond to those issues like that. These set reactions and behaviors are a result of political, social and religious factors that influence them. Although Ayub and Bhutto’s legacies were not fully shattered, it is Zia’s legacies, however, that loom large over Pakistan today. His vision included upholding a shaky democracy under establishment control; using militants expansively to achieve foreign and domestic goals; promoting Salafist Islam to control society; and radicalizing society through madrassas and mosques.

In Pakistan, the situation for women was never very good to begin with, the ideologies espoused in this part of the region, for instance the kind of ones adopted by parents towards their daughters, all predominantly boil down to advocating how daughters ought to be given an average degree of education, enough for them to read, write and speak “fluent English” (2) and then get them married timely in an arranged settlement.

The book opens up in the 1970s, discussing how the “respectable, middle-class, Muslim families” represented a special segment of the community that shared intellectual ideologies, like sending their daughters to the Convent of Jesus and Mary, so that they could be groomed in a pedigreed, yet segregated environment. This represents how the Pakistani society at large, was always a strikingly asymmetrical and demarcated one where the lower social classes were usually discriminated against, as the lower middle-class families could rarely afford to send their daughters to the Convent.

The case of Samina’s murder in the 1970s as narrated in the novel, triggers a sense of dichotomy affiliated with gender roles and expectations, it questions the half-baked and boxed ideologies espoused particularly to rule over women in the highly sexist Pakistani society—preordaining a certain list of things for them to, or, not to do. The notion that Samina was sensitive about her humble class origins, reflects the class inequality and how it psychologically affected a young girl to pathologically lie about it with her girlfriends. The further case of her being given a “boycut” by her family over merely liking and communicating with someone (who lived in East Pakistan) through letters, and subsequently being “honour killed” for it, goads one into understanding how being born a girl in this demarcated society is no less than a punishment. The Convent was a place of enlightenment for Samina; had she been allowed to continue with her studies, she would have matured into a sensible individual, allowing the society to benefit from her individual resource and prowess, however she was silenced brutally, at a very tender age. The novel establishes how even in the Pre-Zia era, life for women was not easy, however there were women who remained within the mainstream even after Zia era and fought for their rights and for the rights and voices of all women around.

With the Sharia and Hudood laws following Zia’s ascent to power, the consequences trickled down to the very bases of the social and cultural fabric, and got deeply absorbed in them, hence worsening the situation further. It was particularly after the Zia regime that women’s status as a class devolved drastically.

In an interview with Asma Jehangir televised in October 2003, she stated:

Why are men not killed in the name of “honour”? Don’t they commit sinful acts and heinous crimes? Why do the men in our society not be concerned about women who are indulged in prostitution, why don’t they marry these women and take them home? Are these women not somebody’s “honour”? This is not “honour”, this is totalitarianism. (Aik Din Geo Kay saath 2003)

The instance in the novel that narrates the case of a girl, Samia, being killed in the name of honour, in Jehangir’s office in 1999, clearly highlights how Samia’s mother, a lady doctor, was deliberately involved in carrying out the murder herself along with her brother-in-law. Nobody could accuse the mother of illiteracy since she was a doctor, and hence it emphasizes the notion that even the regular education delivered at schools and colleges was replete with extremist philosophies associated with the ideologies of “honour” and “integrity” in this region, and they all were acutely intensified during the eleven years of Zia’s rule, as Khan writes:

A man in whose ear God spoke directly, our beloved generalissimo had, with a stroke of a pen and the acquiescence of the mullah-types he stuffed the houses of parliament with to give him the legitimacy he so desperately desired, gotten rid of all the laws meant to protect the rights of women . . . (22)

In an article published in an English daily on December 26, 2012, Dr Abdur Razaque Channa from the Australian National University wrote:

General Ziaul Haq played a significant role in shaping the educational system through his education policies that monitored the syllabi of state institutions. Policies and curriculums designed during that time were based on a rigid representation of Islam. Educational policies in general and textbooks in particular were designed in a way that reflected and disseminated gendered messages favouring males and discriminating against women.

Fawzia’s visit to Lahore in the spring of 2001, made her realise how deeply embedded the Pakistani society had become in a morass of superficies. Her lunch with Saira and Naumana was an eye-opener towards the ever widening gyre of religiosity that had now seeped in the very flesh and blood of these two women, who as little girls, were rather more intellectually sound. The way that Saira and Naumana defend Dr. Israr Ahmed, a misogynistic religious scholar who believed that women were born to confine themselves within the chadar-and-chardeewari of the house, crystallizes the notion that by 2001, religion had dribbled into the mental faculties of the ordinary masses so much that it had become rather impossible for them to have a conversation without it. The fact that Saira and Naumana themselves were articulating in favour of the chadar-and-chardeewari ideology, explains that in the Pakistani society, it was not only the “Women vs. Men”, or the “Women vs. Family” struggle, but also now additionally “The Moderate Women vs. The Extremist Women” predicament to deal with.

Gender Politics

Even in the pre-Zia era, women routinely faced serious restrictions and limitations of autonomy. The gender discrimination that existed during Zia’s time laid the foundations for an upcoming period that was meant to push the country towards devolution, instead of evolution. Even in pre-Zia Pakistan the problem of acute sexism and gender inequality existed within the mentalities of the people, however with the kind of misogynist laws introduced during Zia’s era, things worsened and, in a way got, “Islamically” legitimized. The chaddar-aur-chaardeewari dogma concretized men’s beliefs of imprisoning women within the domestic setups.

Hajira’s treatment is reason enough to believe how women were casted out of working setups and they had no say before their mother-in-laws. Workaholic and talented women were reduced to the domestic chores of cooking and catering the needs of the husbands and their children. The Sharia laws that dispossessed Naumana of her son, indirectly gave the father a privilege over the child, setting precedent for other men that exemplified this as a legitimatized upper hand over women assigned to them as husbands with regards to their power, position and say in a marital relationship.

The novel, at several occasions, provides evidences of Pakistani women being more politically conscious than Pakistani men, but due to the pressing restrictions imposed upon them they were only capable of verbally condemning the political circumstances. Khan writes in retaliation to Bakri’s and Sufi’s attitude:

. . . I want to scream at him—Why don’t you go out on the streets and protest against the martial law which has thrown your man [Bhutto] behind the bars, the man who gave voice to your communist sentiments, his slogan of ‘roti, kapra aur makkan’—a rallying cry for the poor and downtrodden masses you always claim to be fighting for? . . . (48)

Khan states in the novel that Sufi accepted “goodies” from Hajira’s family, like cars and a house, and they, despite being socially moderate and well-moving, had to pay acquiescence to him, this can be clearly perceived as an act of Sufi exploiting his position in society—manipulating Hajira’s parents to his advantage, solely on the pretext of being a husband to their daughter.

Women’s individual pursuits and collective struggles

Not only was the cultural and social ideology now heavily punctuated by state-mandated religiosity which propagated zaniness under the name of ghairat, but also the artistic reservoir that women could resourcefully contribute to, was targeted and women were circumstantially barred from partaking in artistic activities. People started believing that Art-based institutions were a threat to conservative culture. Hajira had a moderate family background, and the idea of her joining the Fine Arts College did not strike her family as a dangerous proposition. In the novel, Khan talks about how Hajira’s choice of attending the Fine Arts College was basically a fulfillment of an individual desire, which could also be taken as the allegorical construction of representing the individual desires of hundreds of young Pakistani women back then who would have wished to pursue the Arts, but the myopic ideology that had been introduced by the mullahs rendered them incapacitated to go after their goals in life. In 2012, distinguished freelance columnist, Adnan Javed, wrote in an online media blog:

The year 1981 was a time when military ruler General Zia-ul-Haq’s martial law was at its height as Pakistan was undergoing a programme of Islamisation that imposed Draconian restrictions on culture and entertainment. With all but the most insipid forms of visual art officially banned as “un-Islamic”.

Because of her association with Sufi, Hajira’s gradual transformation from her secular-minded self to a more Islamically-inclined deportment, could be analyzed at a macrocosmic level. It indirectly explains the transformation of a complete society that took a roller-coaster ride from searing hopes about a secular Pakistan in the 1950s to the shattered illusions of one in which religious bigotry and intellectual-deprivation pervaded in the 1980s. Khan talks about how Hajira was so consciously brainwashed by Sufi’s arguments about religion and of owning roots that she lost the sense of identifying herself. While deprecating her parents’ values, she refused to visit Fawzia in Massachusetts, for she had been told by Sufi how it was a way of “giving up material comfort in pursuit of a classless society” (51). However, it was in actuality Sufi’s tactics of making her gradually move away from the fecundity of life. Once married, Hajira was cut off from her artistic sensibilities, and was made to completely dedicate herself to the needs of the mother-in-law, her husband and her child—a very usual feature of the Pakistani society at large. Cutting Hajira off her artistic sensibilities meant that she was also dispossessed of her right to channelize her intellect and subsequently her right to a lively life. Since she had been made to get attuned to a “simplistic lifestyle”, she also gave up things like wearing well and looking good. This describes how women’s lives could be influenced by the institutionalized gender inequalities in any society, not just a Third World one, as Western feminists deem it as.

Hajira went under a social transformation. She came from a liberal family background and was very open-minded. The fact that she suicided is reason enough to gauge the magnitude of depression that she was going through. The fact that her mother-in-law flushed her medicines, because she believed that lactating the baby was more significant than Hajira’s health and wellbeing, is another instance in the novel that highlights how the ability to be a subservient and demure wife is the primary quality that is observed within girls in this part of the world where they are displayed, as perfunctory beings, to be selected for people’s sons. Published in 2011, an online article entitled “Gender roles and their influence on life prospects for Women in Urban Karachi, Pakistan: a qualitative study”, maintains:

A good woman in Pakistan is expected to do household chores, care for her children, husband and in-laws and when needed provide the home with external income. A woman is expected to hide her emotions, to compromise with her opinions and to sacrifice her own dreams.

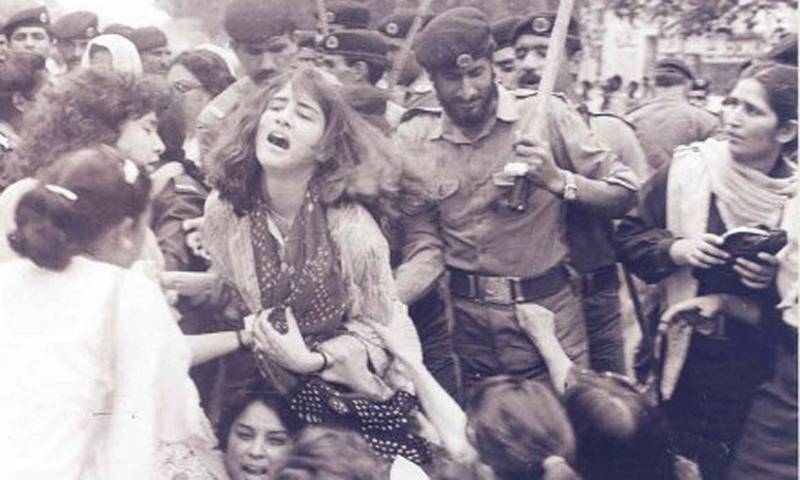

Khan writes about herself in the novel that she became a feminist because of the experiences that her girlfriends in Pakistan went through—the way Samina got murdered, Hajira ended up suiciding and Naumana had her son snatched away by her husband who abandoned her and took their child after seven years of separation, getting away scot free because of the constitutional protection of the Sharia laws that gave any man the right to claim his child anytime, no matter what. The Hudood Ordinance that led to Safia Bibi’s fate transformed a myriad of women into feminists. Women and Human Rights activists were outraged and for the Women’s Action Forum (WAF), formed in 1980, went out onto the streets to protest the punishment sentenced to Safia Bibi, and demanded changes to the laws.

Khan writes:

I feel lucky in retrospect, I wasn’t stoned to death for cavorting with strange men to whom I wasn’t related in the capacity of sister, wife, mother… a fate that has befallen many a woman since the so-called Islamic laws of Hudood curtailing women’s rights in every arena including sexuality were passed by the legislature during Zia-ul-Haq’s military regime in the 1980s. (42)

Khan’s rebellious disposition in the novel is the culmination of a moderate woman’s struggles in this part of the world. From the very beginning, she describes how in Pakistan the social expectations and positions assigned to women are subordinate to men. The “Moddess pads” that Khan talks about in the novel, are a representation of how women are expected to be, as Khan describes, “models of modesty” (30). This rebellious disposition of Khan also informs her resistance to state laws and traditional beliefs, her argument with her mother on the dining table over the Shia issue and her defiance to listen to the dogmatic statements by her mother, in a broader context, represent the struggles of any moderate Pakistani woman against the myopic mindset of the rigid, conventional system. This could be compared to in the 1980s, secular-minded and socially-moderate women of the country suffered the brunt of police action for defying Section 144 to protest against the proposed Evidence Bill during Zia’s regime; the protesting women had planned to march to the Lahore High Court to submit a petition against the bill, which reduced the legal status of women by proposing that the evidence of two women should be equal to that of one man’s.