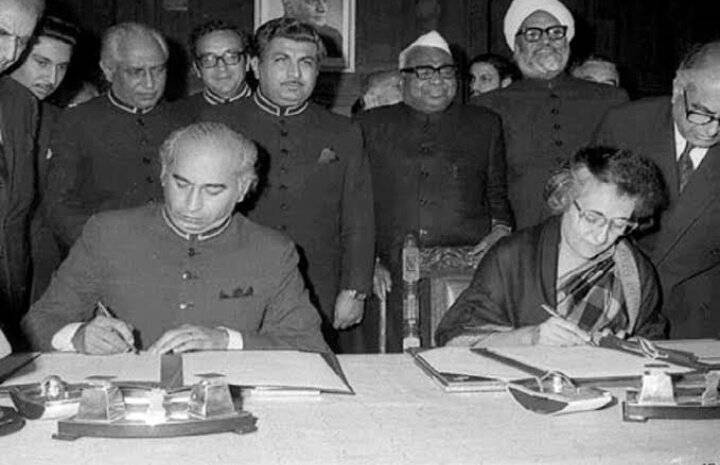

In his farewell speech to the Pentagon in December 2006, Donald Rumsfeld warned that ‘weakness is provocative’. This approach seems to be the beating heart of many powers’ foreign policy and also serves to explain the Simla Agreement. Pakistan signed the pact just after losing a war in which it was dismembered, conceding ground which has only served to weaken its claims since. The agreement itself is a mere six clauses and yet the scholarly ink spilled in its support or critique runs many lengths that. Following India’s abrogation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status in August 2019, the question for Pakistan is whether the Simla Agreement should be given CPR and revived, or whether it is worth withdrawing from entirely.

The Agreement requires India and Pakistan to settle their differences by peaceful means through bilateral negotiations and prohibits either country from unilaterally altering the situation.

In relation to Kashmir, it states that “the basic issues and causes of conflict which have bedeviled the relations between the two countries for the last 25 years shall be resolved by peaceful means” and binds both parties to discuss the modalities and arrangements for durable peace and normalization of relations, including a final settlement of Jammu and Kashmir. Pakistan maintains its desire to talk to India but also solicits international intervention to ensure the implementation of Security Council Resolutions. Its longstanding position has been that Jammu and Kashmir needs to be demilitarized and a supervised plebiscite held. India meanwhile states that the Simla Agreement precludes international involvement in the issue (despite India being the one to take the issue to the UN) and deprives Pakistan of locus standi from intervening in Kashmir. India also contends that local elections in Kashmir (held under the eyes of its huge army, which have been marred by violence, boycotts, and accusations of rigging) are the same as a plebiscite.

Pakistan’s main grievance is that by abrogating Article 370 and balkanizing the territory into two separate states, India has unilaterally altered the situation in violation of the Simla Agreement.

However, the international community has alarmingly seemed to side with India largely due to its desire to not rankle this regional power too much. When China convened a closed-door meeting of the Security Council to discuss the issue, Russia and France cited the Agreement when vetoing a resolution tabled during the meeting. The UN Secretary-General also recalled the Simla Agreement when appealing for maximum restraint between the parties following the tensions that ensued in August 2019.

India’s talk of bilateralism is confrontation masquerading as cooperation. It has merely served to exclude outside involvement in an issue India has no desire to solve. Relying on the Simla Agreement is a gross cop-out which ignores the fact that while the pact refers to meetings between ‘Heads’ which would resolve disputes, these meetings have happened only a few times. Talks have then stopped or stalled and there were never any serious efforts to resolve the dispute. In fact, the Agreement has led to this issue being more deeply entrenched, creating a perpetual stalemate as one side cannot talk about Kashmir when the other refuses to engage and then annexes the territory to its own.

Pakistan has continued to court international intervention, drawing attention to the genocidal saffron policies of the BJP and its ‘settler laws’ in Jammu and Kashmir. These have not really worked and India is now an aspiring superpower longingly eyeing a permanent seat at the Security Council. In abrogating Article 370, it is also acting to ensure that it will not be refused a seat due to its inability to resolve the Kashmir dispute. It also aims to preclude a mediator as given its powerful status, it is wary of the equal treatment which would be given to both sides in a mediation. It has stopped engaging with even the UN’s Military Observer Group to India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) following the Simla Agreement, leaving only Pakistan reporting to the organization which is largely toothless due to India’s refusal to participate.

So, what should Pakistan do? We are currently again in a weak position, with First World moneylenders at our throats our economic situation will worsen and our defence budget will be cut (while India side-eyeing China has anxiously increased its own by 13 percent). However, Pakistan should look to thwart India’s long term goals. It can seek China’s support in countering India’s bid for a permanent SC seat due to the Kashmir dispute. Moreover, it can also publicise its attempt to bring India to resolve the issue bilaterally through a mediator. While the US and Russia would not be acceptable to either state, the Gulf States may have an increasing role to play.

The ceasefire on the Line of Control agreed to in February 2021 was facilitated by the UAE, with the country’s ambassador to the US claiming he had helped arrange meetings between Indian and Pakistani intelligence chiefs in finalising the truce. The UAE may be an acceptable mediator to both Pakistan and India, though Pakistan should be wary of increasing economic cooperation between the two states. Moreover, a key issue with the Simla Agreement is its lack of specific mandated mechanisms. In a last ditch effort to save the agreement and abide by the need for bilateral cooperation inherent to it, Pakistan should look to draft an actionable sub-agreement under Simla similar to the Good Friday Agreement between Ireland and the UK regarding the status of Northern Ireland and distribute it in order to force India to the table. This sub-agreement should provide a framework which structures in detail how difficult issues will be addressed and discussed, including issues relevant to both sides, namely demilitarisation, policing, and self-determination. It could also detail the continuation of the Line of Control as a de facto border. The Simla agreement’s relevance seems to be predicated on the fact that it delineates the Line of Control between the two countries, however, the text understands this to be a de facto border, not a de jure one. Pakistan should include in any new sub-agreements its intention to continue to respect the de facto border. If India does not agree to this framework agreement, which is likely, then Pakistan should withdraw from the Simla Agreement and seek to internationalise the dispute once again.

The focus of Pakistan’s argument should be highlighting that legal title for Jammu & Kashmir has not passed to India. The Security Council Resolutions and India’s own constitutional history clearly reflect this position. As such, Pakistan must make every effort to reverse India’s 5 August 2019 gameplan which is aimed at ‘internalising’ the matter and changing the goalposts so that Kashmir issue no longer remains a ‘dispute’ under international law. While most of the international community no longer views the 1950’s formula of a UN-supervised plebiscite practical today, Pakistan must not forget the real value of the UNSC Resolutions in that they crystallise Kashmir as a disputed territory under international law where title has not passed to either India or Pakistan.

Pakistan’s withdrawal from Simla would be valid under international law. This is because India, in annexing and bifurcating the disputed territory, has committed a material breach of the agreement. Article 60 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties defines a material breach of a treaty as the violation of a provision essential to the accomplishment of the object or purpose of the treaty, which in this instance would be a unilateral act which does not accord with bilateralism. Withdrawing after having attempted to create a sub-agreement and appoint a mediator would indicate that Pakistan has attempted to uphold the obligations under the treaty as much as it could, leaving withdrawal as the only remaining option.

In the early decades following partition, the Kashmir issue was overwhelmingly viewed as an international dispute on the UN agenda. Simla provided India with the perfect excuse to ‘bilateralise’ the dispute. The treaty has, so far, only been an obstacle to Pakistan’s attempts to ‘internationalise’ the Kashmir issue which India uses to roadblock the discussion of Kashmir as well as other issues such as Sir Creek. On 5 August 2019, India has once again moved to change the goalposts, and is now trying to portray Kashmir as an ‘internal’ matter. Countering the Indian juggernaut will require Pakistan to develop a bold Kashmir policy based on sustained diplomatic, legal, and academic engagement with the international community and effective media and strategic communication strategy for mobilizing public support at home.

After all, while weakness is provocative, history proves that Goliaths can be beaten.